Tags

In this first installment of Women 101, the 2018 edition, I present politicians and political wives, specifically presidential candidates and first ladies. One of the main reasons I started this series last year was because of the deeply ingrained misogyny revealed by the 2016 presidential election and so it seems only fitting to take a look at how women and their involvement in presidential politics and elections have fared in the past. I had hoped to post this on International Women’s Day but I’m afraid a different civic duty—namely, jury duty—intervened.

Foundational Support

In terms of presidential politics and policies, two women stand out among the Founding First Ladies: Abigail Adams and Dolley Madison. In one sense, they represent diametrically opposed visions of the First Lady role, with Abigail Adams as the intellectual policy wonk advisor to her husband (à la Eleanor Roosevelt and Hillary Clinton) and Dolley Madison as the consummate hostess and savvy socialite (à la Jackie Kennedy). Of course, the real story is likely much more nuanced. Unfortunately, unlike for Abigail Adams, I could not easily find serious, reputable works on Dolley Madison that might tell us more about this fascinating woman.

Abigail Adams (1744–1818)

Abigail Adams, née Smith, is likely the best known of the women whose short biographies I will be presenting here. Wife of John Adams, the second U.S. president, and mother of John Quincy Adams, the sixth, she is one of the few women commonly recognized as one of the founders of the United States. Although she received no formal education, Adams came from a family active in Massachusetts politics and New England society and this afforded her the opportunity and resources to pursue a more intellectual life than was common for women of her day. As anyone who has watched the HBO mini-series John Adams (based on the book by historian David McCullough) knows, Abigail was a close advisor to her husband and their correspondence is a treasure trove of information about the American Revolution, the formation of the U.S. government, and other political matters.

While there seems to be some dispute about how “feminist” Adams actually was, she certainly advocated for better educational opportunities for women as well as laws in their interest. In this regard, her March 1776 letter to her husband, requesting that he “remember the ladies” while at the Continental Congress, is often cited. What is less well known about Adams is that she was an extremely savvy investor (although sometimes ethically questionable), speculating in both bonds and land. Since her husband was often away from home, first due to his law practice, and later to his political activities, Adams managed both the family farm and finances, investing so wisely that some argue she is largely responsible for the family’s wealth. For anyone interested in learning more about this aspect of Abigail Adams’s life, check out the Ben Franklin’s World podcast listed below, or the work of historian Woody Holton.

It is really mortifying, sir, when a woman possessed of a common share of understanding considers the difference of education between the male and female sex, even in those families where education is attended to… Nay why should your sex wish for such a disparity in those whom they one day intend for companions and associates. Pardon me, sir, if I cannot help sometimes suspecting that this neglect arises in some measure from an ungenerous jealousy of rivals near the throne.

—Abigail Adams to John Thaxter, 15 February 1778

Dolley Madison (1768–1849)

Dolley Madison, née Payne, was the wife of James Madison, the “Father of the Constitution” and fourth president of the United States. Raised as a Quaker, Dolley had grown up on a slave plantation in Virginia; however, in the wake of the Revolution, her father emancipated his slaves and moved the family to Philadelphia. It was in Philadelphia that she met and married her first husband, John Todd, in 1790. Todd was a Quaker lawyer who quickly provided Dolley with two sons but who unfortunately contracted yellow fever in the summer of 1793 and died, along with their younger son, in October of that year. In 1794, she married Madison, at the time a bachelor of long standing and seventeen years her senior. Since Madison was not a Quaker, Dolley was expelled from the Society of Friends for marrying him. Just a few years later, Madison retired from politics and moved back to Montpelier, the Madison family plantation in Virginia. However, his retirement didn’t last for long, and he was called back to public service by President Thomas Jefferson to serve as his Secretary of State.

As the first presidential wife to occupy the White House for an extended period of time (and having often served as official hostess for the widowed Jefferson), Dolley did much to define the role of what would come to be called the First Lady, including helping to refurnish the White House after the original building was almost completely destroyed by fire during the War of 1812. She is also credited with making sure that the famous Lansdowne portrait of George Washington was saved from the fire. In contrast to her serious and reserved husband, Dolley was known for being a charming hostess who could bring politicians of all stripes together. She was extremely popular in Washington and, to this day, is the only citizen to have received an honorary seat in Congress. Unfortunately, her son Payne was a bit of a wastrel and was responsible for the family’s money troubles later in life. After her husband’s death in 1836, Dolley would organize and copy his papers in the hopes of selling them to Congress to raise money, but was eventually forced to sell Montpelier to pay off outstanding debts.

Blazing the Trail

As we leap ahead to the late nineteenth century, we come to two different women who ran for president: Victoria Woodhull and Belva Lockwood. In other words, we have come to the portion of this post where I start screaming about wanting a movie about someone. Because why have I never really heard of these women before? Woodhull, especially, is utterly fascinating, but both these trailblazers should have multiple books, historical monographs, and films dedicated to them.

Victoria Woodhull (1838–1927)

I think one reason Victoria Woodhull, née Claflin, is sidelined in the historical record in favor of other more prominent suffragists is that she was just too darn controversial. She had a shady background complete with a con-man father and her first “career” was as a medium under his tutelage. As a candidate, she spoke about “radical” reforms such as public education and welfare for the poor as well as taboo subjects like marital rape and free love (by which she meant free will and partnership in marriage, not the hippie variety, but was nevertheless scandalous for her day). At the same time, Woodhull was quite the rags-to-riches story. This was due in large part to her connection to Cornelius Vanderbilt, whom she met in the company of her sister Tennessee in the context of their work as a spiritualist and a “healer” respectively. It is rumored that Vanderbilt both had a long-standing affair with Tennessee and gave Victoria the stock tips that provided her with the income necessary for the two-part campaign she planned to wage. Phase One was to achieve financial stability along with respectability, since it hadn’t escaped her notice that other suffragist leaders were from the educated, leisure classes. Phase Two was to become President of the United States.

The first phase was set in motion when the stock market crash of 1869 enabled Woodhull to buy up stocks on the cheap. Again with help from Vanderbilt, who invested $7000 dollars in the sisters, Victoria and Tennessee became the first women in the country to own and operate a Wall Street brokerage firm. In this effort they were supported and assisted by Woodhull’s husband, James Blood, who was trained as an accountant. Just months after opening their firm, in April 1870, Victoria bought a mansion on the right side of the tracks and declared in the New York Herald her intentions to run for president. One month later, the sisters became the first women to found a weekly newspaper, which Victoria used to champion her causes and candidacy, including granting women the right to vote. (This was on the heels of the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment.)

To further her cause, in 1871, Woodhull became the first woman to speak before Congress, testifying before the House Judiciary Committee regarding women’s suffrage. There, she presented the argument that under the Fourteenth Amendment, as persons born in the United States, women were citizens, and, as citizens, under the Fifteenth Amendment, they already had the right to vote. In this fight, she was initially supported by other suffragists such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. However, Victoria’s interest in a broader progressive platform and her tendency to attract scandal led to a break with these leaders. Eventually, Woodhull ran for president of the United States in 1872 as the candidate for the Equal Rights Party. Abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass was nominated as the vice-presidential candidate, although he did not attend the convention and never acknowledged the nomination. Some question whether Woodhull should be granted the status of first woman to run for president because, at the time, she was only thirty-four years old, i.e., not the constitutionally mandated age of thirty-five. Nor did she appear officially on the ballot. Regardless, the press treated her as a legitimate candidate. Unfortunately, just days before the election, she was arrested on obscenity charges for publishing an account of Congregationalist minister Henry Ward Beecher’s adulterous affair. So Woodhull could not even attempt to vote for herself in the election. She won no electoral votes and only a negligible amount of the popular vote. Dogged by scandal, she eventually moved to England, where she led a relatively quiet life, living to see women gain suffrage in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

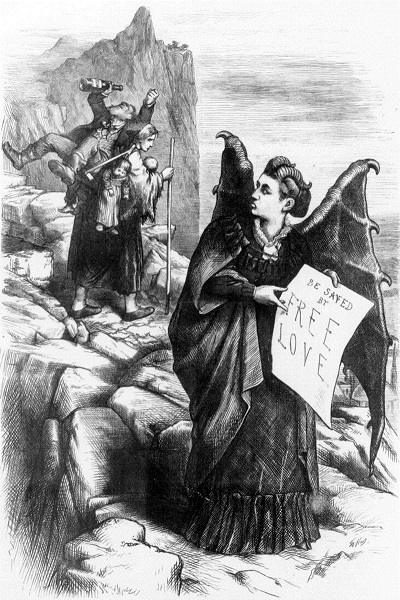

You know you have made it when there is a nasty political cartoon about you. In “Get thee behind me, (Mrs.) Satan!” Thomas Nast depicts Woodhull as a devil trying to tempt a hard-working woman, who claims “I’d rather travel the hardest path of matrimony than follow your footsteps.”

I ask the rights to pursue happiness by having a voice in that government to which I am accountable.

—Victoria Woodhull, February 1871

Belva Lockwood (1830–1917)

Belva Lockwood, née Bennett, is the other woman who might rightfully claim the title of first woman to run for president. Born on a farm in upstate New York, by the age of 14, Belva was teaching at the local school. By 18, she had married a local farmer. In 1853, her husband died of tuberculosis and, needing to support herself and her daughter, she decided to go to college. Suffice it to say, most of her friends and family thought this was a crazy plan since most schools did not even admit women at that time. Nevertheless, she persisted. That persistence paid off and she managed to convince Genesee College (now Syracuse University) to admit her; she graduated with honors in 1857. She planned to make a career in teaching and administration, however, once she found out that women were paid half of what men in the same positions were paid, she turned her sights on the law. This turn was also likely influenced by meeting Susan B. Anthony.

In 1866, Lockwood moved to Washington, D.C. to pursue this new avenue. Two years later she married Reverend Ezekiel Lockwood, a minister and dentist twenty-nine years her senior who shared her progressive values and supported her ambition. Because of her gender, Belva struggled to gain admittance to law school, and later would even struggle to get the diploma she earned, without which she could not be admitted to the bar. After appealing to President Ulysses S. Grant, she did get the piece of paper and was admitted to the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia in September 1873, becoming one of the first female lawyers in the United States. However, upon her application for admission to both the United States Court of Claims and the U.S. Supreme Court, she was denied access on account of her gender. So what did she do? She drafted an anti-discrimination bill to have the same access to the bar as male colleagues and, for the next five years, lobbied Congress to pass it. In 1879, President Hayes finally signed the law, allowing all qualified female attorneys to practice in any federal court. On March 13, 1879, Lockwood became the first woman to be admitted to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court and, the next year, became the first women to argue a case there. Intersectional before intersectionality was cool, she later sponsored Samuel R. Lowery to the Supreme Court bar; Lowery would go on to become the first black attorney to argue a case before the Court. Lockwood would later advocate on behalf of the Eastern Cherokee in United States v. Cherokee Nation (1906), eventually winning them a $5 million judgment for treaty violation. I mean, damn, girl.

Not content with all her legal activism and advocacy for women’s issues, and angered with the refusal of both major parties to include an Equal Rights plank in their platforms, Lockwood ran for president in 1884 and 1888 on the Equal Rights Party ticket. Her platform included such issues as balanced marriage and divorce laws, citizenship for all Native Americans, and a policy that favored peace over aggression. Lockwood knew that as a third-party candidate without women’s suffrage she had no chance of winning (in the end, she received about 4100 votes), but she was able to parlay this exposure into a lucrative career and progress on numerous pet issues, particularly peace and disarmament.

The Unbossed

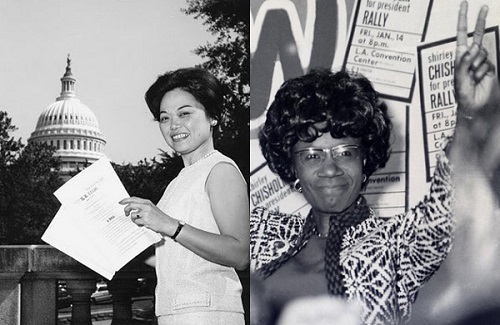

Two women I learned about primarily through editing an American Government textbook (and seeking to add photos of women and people of color wherever I could) are Shirley Chisholm and Patsy Mink, who were both among the fifteen people to officially declare their candidacy for the 1972 Democratic Party presidential nomination. I’m sorry I didn’t learn more about these women when I was younger—they did so much for the cause of civil rights and are such great role models for anyone looking to be a catalyst for change. In any case, I was quite happy to see Senator Kamala Harris (D-CA) and Representative Yvette Clarke (D-NY) announce on Tuesday that they are co-sponsoring a bill to have Chisholm recognized with a statue in the U.S. Capitol.

Shirley Chisholm (1924–2005)

Shirley Chisholm, née St. Hill, was born in New York City, and, although she spent some of her childhood living with her grandmother in Barbados, spent most of her life in Brooklyn as an educator and activist and eventually as a congressional representative. After paying her dues in the local political arena and state legislature, in 1968, Chisholm ran for U.S. Congress in New York’s newly created 12th District with the slogan “Unbought and Unbossed” and became the first black woman elected to the U.S. Congress, eventually serving seven terms. She was a founding member of both the Congressional Black Caucus and the National Women’s Political Caucus. During her time in Congress, Chisholm only hired women for her office, half of whom were black. While there, she worked tirelessly on behalf of the poor, educational programs and other social services, equal rights for women, and anti-discrimination laws. She opposed American involvement in Vietnam and the draft.

In 1972, she became the first black candidate for a major party’s nomination, and the first woman to run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination (Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine had run for the Republican presidential nomination in 1964). Chisholm had difficulties gaining ballot access, but campaigned or received votes in primaries in fourteen states and won twenty-eight delegates during the primaries process itself. She received little support from the Democratic establishment, including black male colleagues. Nevertheless, Chisholm won a total of 152 first-ballot votes at the national convention, or fourth place in the roll call tally. She was initially supported by Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, but the politics of “who can actually win” eventually reared its ugly head and, in the convention battle between Hubert Humphrey and George McGovern, McGovern came out on top. Of course, McGovern then went on to lose the general election in spectacular fashion, winning only seventeen electoral votes.

The Constitution they wrote was designed to protect the rights of white, male citizens. As there were no black Founding Fathers, there were no founding mothers — a great pity, on both counts. It is not too late to complete the work they left undone. Today, here, we should start to do so.

—Shirley Chisholm, speaking on behalf of the ERA, 10 August 1970

Patsy Mink (1927–2002)

Oddly enough, Chisholm was not the only woman to run for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination. That same year, Patsy Mink, née Takemoto, a representative from Hawaii, also announced she would run, primarily as an anti-war candidate. In so doing, she became the first Asian American to run for the Democratic presidential nomination. Unfortunately, because she had to focus on her reelection in Hawaii due to a conservative Democratic challenger, her campaign was much more limited than Chisholm’s—she only stood in the Oregon primary and did not receive any delegates.

Mink seemed destined for politics from an early age: In high school, she managed to win her first election, to become student body president. How was this unusual? She was the first female candidate ever. She was Japanese American. The election was a month after Pearl Harbor. Later, she graduated as class valedictorian. After first attending college in Hawaii, she eventually transferred to the University of Nebraska, where she created a coalition that successfully lobbied to end the school’s segregation policies. Stymied in her attempts to attend medical school while female, Mink chose to attend law school at the University of Chicago instead. There she met her husband John Mink and earned her J.D. in 1951. The family soon moved back to Hawaii, where Mink became the first woman of Japanese descent to practice law in Hawaiian territory. Soon she became involved in local politics.

After Hawaii became a state in 1959, Mink served as a Hawaiian delegate to the 1960 Democratic National Convention, where she gave a powerful speech about civil rights. In 1965, Mink became the first Asian American woman to be elected to Congress. She would serve a total of twelve terms. Mink was the author of numerous laws in favor of equal rights but is best known as a co-author and sponsor of the Title IX Amendment of the Higher Education Act. After her sudden death in 2002 from complications arising from chickenpox, this act was renamed in her honor to be the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act.

It is easy enough to vote right and be consistently with the majority. But it is more often more important to be ahead of the majority and this means being willing to cut the first furrow in the ground and stand alone for a while if necessary.

—Patsy Mink, 8 October 1975

As I often feel after these write-ups, I’m sad I didn’t learn more about these women earlier in my life. But I suppose better late than never. Is this just me? Did you know much about any of them? If so, where did you learn what you learned?

To read more about these incredible women:

- Thomas J. Fleming, The Intimate Lives of the Founding Fathers (2009)

- Catherine Allgor, A Perfect Union: Dolley Madison and the Creation of the American Nation (2006)

- Natalie S. Bober, Abigail Adams: Witness to a Revolution (1995)

- Woody Holton, Abigail Adams (2009)

- Rosemarie Zagarri, Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic (2007)

- Cari Carpenter (ed.), Selected Writings of Victoria Woodhull: Suffrage, Free Love, and Eugenics (2010)

- Mary Gabriel, Notorious Victoria: The Life of Victoria Woodhull, Uncensored (1998)

- Lois Beachy Underhill, The Woman Who Ran for President: The Many Lives of Victoria Woodhull (1995)

- Jill Norgren, Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would Be President (2007)

- Ellen Fitzpatrick, The Highest Glass Ceiling: Women’s Quest for the American Presidency (2016)

- Shirley Chisholm, Unbought And Unbossed (1970)

Podcast episodes:

Ben Franklin’s World: Abigail Adams: Revolutionary Speculator

Election College: Abigail Adams

History Chicks: Abigail Adams; Abigail Adams Feminist

Election College: The First First Lady: Dolley Madison

HerStory: Dolley Madison

History Chicks: Dolley Madison

HerStory: Victoria Woodhull

History Chicks: Victoria Woodhull

Stuff You Missed in History Class: Victoria Woodhull

History Chicks: Belva Lockwood

History Chicks: Shirley Chisholm

Stuff Mom Never Told You: Fighting Shirley Chisholm

For previous posts in this Women 101 series, click below:

From Abigail Adams to Zenobia

Birds of the Air

Wasps and Witches

Soldiers and Spies in the Civil War

Soldiers and Spies in World War II

Adventurers and Explorers

For the next post in this series, see A Mind at (House)Work.